The Origins Of Aston Martin’s V12

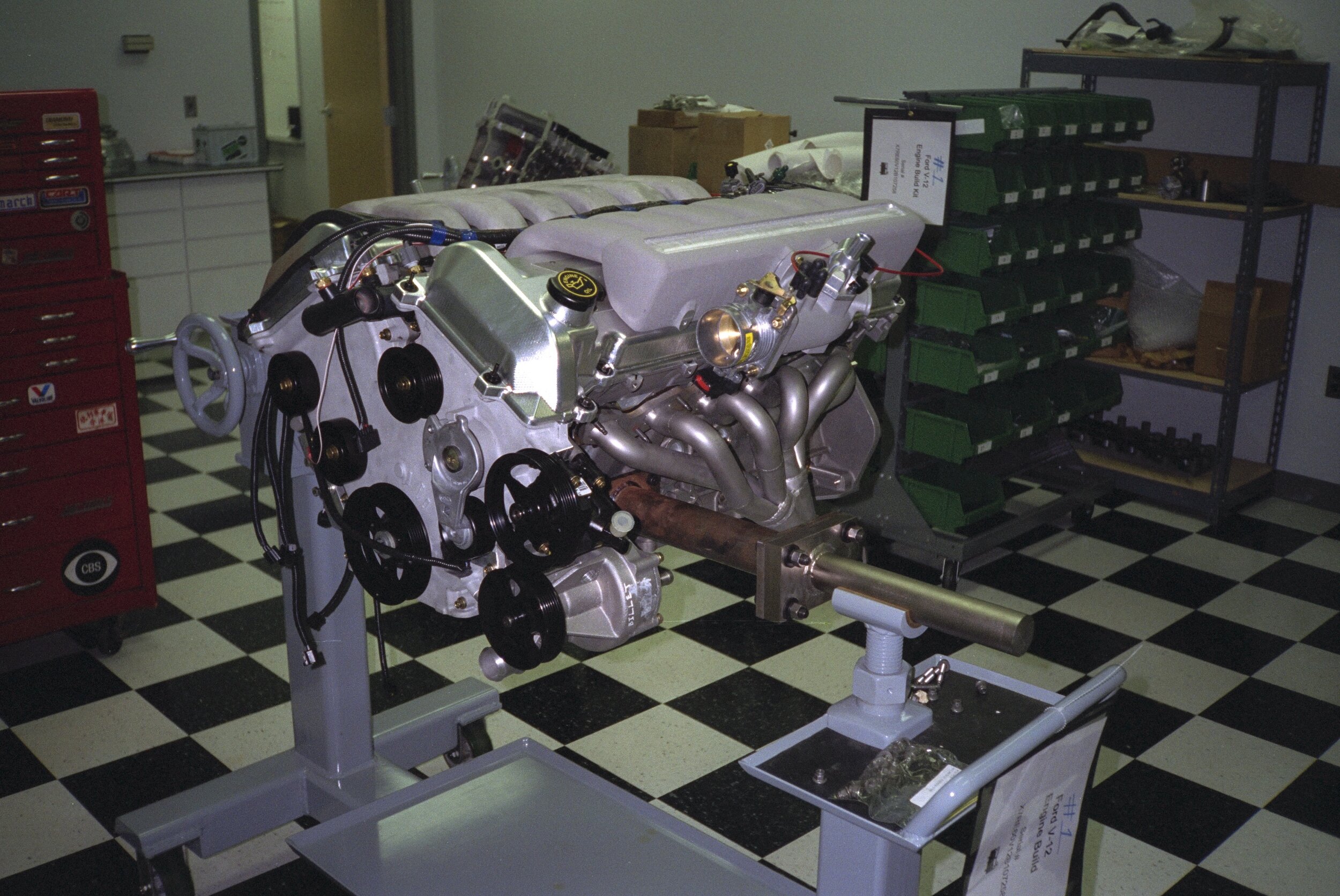

The first V12 DB7. The car was an I6 fitted with the V12 and Borg Warner (now Tremec) T56. Vantage improvements were not fitted to this chassis.

This article is reproduced with the kind permission of the Aston Martin Heritage Trust and was first published in ASTON #21 in December 2019. ASTON is the AMHT’s annual publication and has won numerous awards for its writing and excellent, unique articles. The AMHT was formed in 1998 as an education charity with two main goals. Firstly to collect and preserve the rich history and heritage of Aston Martin through huge photographic and document archives together with an extensive collection of artefacts and cars. The second goal is to share that story with the public through the Aston Martin Museum and with researchers, authors, TV producers, owners and of course, Aston Martin Lagonda themselves. Learn more about the AMHT at http://amht.org.uk.

I am often asked, what is my proudest achievement from working on the Aston Martin V12? As a young engineer looking forward, a few things immediately come to mind: challenging Ferrari, winning at the Le Mans 24 Hours or restoring Aston Martin to a prominent position on the world stage. All were wonderful things to be a part of, particularly since one of my childhood heroes, Carroll Shelby (who I had the honour of meeting a number of times), had a big role in achieving similar successes with the British company.

But with experience and hindsight you understand that your original goals may not be the most important. In fact, I didn’t recognise the real high point until many years after the event. We had just installed the V12 in the first DB7 Vantage prototype earlier in the week and everyone knew we had a winning product on our hands. One of the AML workers commented to me that he had been at AML a long time and the whole Aston Martin ‘family’ had been through uncertain times. But with the new V12 it was suddenly fun to come to work again.

I knew exactly that, for the first time in a long time, he could see a stronger future. It was only looking back, years later, that I realised that being part of helping so many people at AML have a bright future once again is by far my proudest achievement of the entire V12 programme.

Anthony Musci, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA October 2019

Over the years I have read a lot in the media, seen many TV features and heard much said about the background story of the Aston Martin V12. None of these accounts even comes fairly close to a historically accurate one. There are many reasons for this: the large number of seemingly conflicting pieces of information in circulation, the secrecy of the project at the time — even internally at Ford — and the many Ford-related V12 concept cars from that era. All could cause confusion, particularly to those lacking insider knowledge and an understanding of what’s needed to bring a new V12 from concept to a solidly engineered and practical design.

The original 'Three Guys' (Bernard Ibrahim, second left, the author in the striped shirt and Don Nowland, fourth left) with Chris Zucker, Luis Cattani and John Hahn, without whom we wouldn't have been able to accomplish what we did.

Whilst by no means a complete account (that would take at least an entire book) this is an overview of how the AML V12 really came about...

I had the pleasure and privilege of starting the Aston Martin V12 engine programme as a young engineer at the beginning of my career. I did not know where it might take me, but I had a sense that it could be, if well executed, the revival of a famous brand. It wasn’t just me, of course, there was an indispensable team within Ford Motor Company (FOMOCO), Aston Martin, Jaguar, parts and software suppliers etc, without whom the V12 programme would never have come to be. But that’s getting too far ahead.

Arguably, the origins of the late 1990s production Aston Martin V12 can be traced back years earlier to an experimental V12 from Ford Advanced Powertrain. It was summer 1990 and my second year working as an intern at FOMOCO in Dearborn, this time at Ford Advanced Powertrain Engineering. I was shown a running 90deg, 5,927cc V12 prototype created by precision-welding together sections of blocks and heads from two development Ford 4.0-liter Modular V8s (The 4.0-liter was expanded in early development and launched as the 4.6-liter V8). It was testing the waters for a Ford V12. Several were built and the first was installed in a Lincoln Town Car with a specially modified Ford automatic four-speed. A number of years later, one of these engines was modified and used in the Ford GT90 show car presented on the 1995 show circuit, which we will return to later.

As luck would have it, prior to my graduation with a degree in Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering in spring 1991, FOMOCO offered me a full-time position. Late summer that year I started at Ford as an employee, joining Ford’s FCG (Ford College Graduate) Programme, a fantastic opportunity for a young engineer that gave new graduates the opportunity to rotate around the company for two years. I worked in factories, test facilities, component design, systems design, product planning etc, all of which gave me exposure to many aspects of the business. Further, it grew my network throughout the company and quickly proved its worth.

During 1992, Jim Clarke (Chief Engineer of Ford Advanced Powertrain) was looking once again at a compact, world-class Ford V12. This time he considered the soon-to-be-released 2.5-liter, all-aluminium, four-valve, 60deg DOHC V6 as its basis. In production, it would be known as the Duratec V6 and debut in the Mondeo (Ford Contour and Mercury Mystique in North America). At first a 2.4, Porsche led the Duratec’s initial design and development. It was a compact, light and state-of-the-art unit combining high power with excellent durability. Unsurprisingly, it influenced the Stuttgart company when it designed the first water-cooled flat-six for the 1996 Boxster.

To meet Clarke’s request for a ‘quick study’ on the possibilities, ECS Roush (Roush Industries today) was tasked to quickly put together an ‘external package study’ engine. At ECS Roush, Jerry Wagner contributed in making the first V12 concept engine by welding three sections of Ford's new 2.5-liter Duratec V6s together. It was simply to provide the package space required for a V12, not to be a running engine. Clarke obviously liked the idea and had some of his team at Advanced Powertrain transform the engine from the package study Roush had done to a show-quality concept engine, still by no means functional.

Aston Martin launched the DB7 at the 1993 Geneva Motor Show and it was also decided to showcase a concept. That was the Aston Martin Lagonda Vignale, and Clarke’s study was shown alongside it. Moray Callum designed the Vignale whilst at Ghia; his brother Ian penned the DB7. That show engine was actually 5,088cc, but since it was two Duratecs most (incorrectly) thought of it as a ‘5.0-liter V12’.

A close look at this unit reveals a few peculiarities. The FEAD (Front End Accessory Drive) had an alternator, hydraulic power-steering pump and an A/C compressor — exactly identical to the 2.5-liter V6 first-generation Mondeo. What this V12 didn’t have was a water pump. Incredibly, nobody noticed! In the Mondeo the water pump was driven by a small belt on the back of an overhead intake camshaft. For the V12 display engine it was simply eliminated. What was noticed by many in the press was that the display engine never had its weld lines fully hidden. This started the rumour that the production engine is ‘just two welded-together V6s’. There are many technical reasons why that approach would never work very successfully if creating a V12 from two 60-degree V6s.

The Vignale was based on the Lincoln Town Car, a relatively simple transition to make a concept since the original was body-on-frame that could be removed to reveal a fully functional rolling chassis with powertrain. Two were made (1) and utilised the donor car’s 4.6-liter two-valve V8 and four-speed auto. Selected members of the press were permitted to drive the Vignale, but access to the engine bay was restricted, as the hood (bonnet) pull was disconnected. No one could notice its lack of V12. A third, fully functioning car (2) was later handbuilt at Newport Pagnell.

On the 1993 international motor show circuit, both six-cylinder DB7 and V12 Vignale generated considerable attention for AML. The original 1993 press release stated: “Drawing on the worldwide resources of the Ford Motor Company, Aston Martin engineers have identified an advanced concept for a V12 engine which could be developed for the Lagonda Vignale.” With just the display-only show unit, Clarke was determined to take matters to the next step.

Towards the end of 1993, FCG rotation programme over, I was a full-time member of Ford Advanced Powertrain Engineering in Allen Park, Michigan. One of my first assignments was to take the architecture of the Duratec V6 and see just how light we could make a small run of test engines, including one for display on the 1994 show circuit, from a whole range of advanced materials. Dow Chemical had just developed a new magnesium alloy (ZC63-T6, or just ZC63) that really drove the idea. So, working closely with the Ford Advanced casting team, I designed a 2.0-liter version with cylinder block, heads and cylinder-block bedplate all cast in ZC63 by specialist Eck Industries (3). With the 2.0-liter magnesium V6 engine prototypes made, I needed to get a cutaway of the engine and I had the good fortune of finding Al English of Cutaway Services, who put together a great version for the motor show circuit that year.

Meanwhile, there was still the 90deg V12 for the Lincoln Town Car based on the 4.0-lite model, now 4.6-litre V8 family, under development. Even though it was fundamentally balanced, it was an ‘odd-fire’ engine with a common pin crank design. It was wide — remember, we had not yet launched the compact 60deg V6. Although Ford was still deliberately short on details of the 1993 show circuit V12, we knew the new Duratec had many desirable characteristics upon which to base a new V12.

At the same time, work was continuing on Jim Clarke’s V12 at Ford’s EMDO (Engine Manufacturing Development Operations) facility at Allen Park, Michigan. I had only just recently readied the show-circuit 2.0-liter magnesium cutaway and was wandering through EMDO to see what new engines were being worked on. I came across a V12 being prepared for Clarke that this time used two of the in-development 3.4-liter SHO (Super High Output) Ford/Yamaha JTT (Joint Technology Team) V8s. I was very familiar with this powertrain, as I had completed one of my earlier FCG rotations with the JTT and knew this approach was not going to work very well, so wrote an internal memo directly to Jim Clarke.

The memo to Jim Clarke that started it all.

Since I was young and stupid, I saw no possible issues with writing a memo directly to the chief engineer (several levels above my boss) of Ford Advanced Powertrain Engineering. I also had my then boss, Bob Natkin, sign the memo as I routinely had Bob sign documents for me in the course of normal business. About a week later, Natkin comes to me and says, quite surprised, “Jim Clarke wants to see you and me in his office tomorrow.” I replied that I was sure it must be about the memo. What memo? The one I wrote, and had you sign! Bob just about had a heart attack when I showed him a copy, and I realised that he never read through in detail what I had him sign.

I had seen Jim Clarke before but when I walked into his office in January 1994 that was really my first time meeting him in person. “Who the hell are you?” he asked. I promptly explained that I had seen the prototype V12 hardware at EMDO and wanted to bring a few critical issues to his attention. Much later, I realised what Jim saw before him was a young and highly motivated junior engineer who was one of the few people that would tell him, unvarnished, exactly what he was thinking — not what he thought the big boss wanted to hear! I presented an alternative plan that would create an all-new V12 unique for Aston Martin Lagonda, but still allow us to leverage a lot from the company showcasing the best of Ford in AML products. By the end of that meeting Jim gave me the green light to see what I could come up with. I believe that was the day that the AML V12 was truly born, as I set out on a new direction for a V12 that would be the basis for a new era at AML. The first reaction from my boss Bob once we left Jim’s office was that he didn’t want this to take too much of my time. I thought to myself, “Is he joking? This is going to be a lot of work”. But I let it go and quickly formed a good rapport with Clarke who was always looking for progress. I put a rough plan together that called for an all-new block, cylinder head and crankshaft designs using the piston assemblies and valvetrain components from the upcoming V6 Duratec family. I also quickly proposed shifting the base V12 from using 2.5-liter components to the 3.0-liter that was to debut later. They both had the same 79.5mm stroke but differed in bore (82.4mm vs. 89.0mm). I knew the increased displacement would be more appropriate, especially for the large Vignale.

It is important to understand this was not an official programme in any sense at FOMOCO. My personal goal every single day was to not get the programme cancelled by the end of it. In the first few weeks I was able to go back to Clarke and request additional CAD (Computer Aided Design) personnel to speed the process along. Seeing enough progress, he quickly agreed. At this point, I had all the engineering for this new, still-unofficial engine as my responsibility, but as it was quickly becoming a serious effort and gaining momentum, we needed to grow the team so quickly added young engineers Don Nowland and Bernard Ibrahim. All three of us were in our early twenties and saw this as a fantastic opportunity to use our engineering skills. We’d already all participated in the Formula SAE (in Europe, Formula Student) racing design competition, which quickly gave us the opportunity to build up a great rapport.

We quickly split up the general (but often shared) responsibilities as follows:

• Don Nowland: cylinder heads, ports, chambers, intake manifolds, throttles, valvetrain and cams.

• Bernard Ibrahim: throttles, exhaust manifolds, front-end accessory drive, front cover and electronic controls

• Anthony Musci: cylinder block, oil system (and pump), cooling system (and pump), pistons, rods, crankshaft and electronic controls.

Often there was overlap, such as in the cooling system, where we all had a hand at some point in aspects of the design. Each of us were fully familiar with all of the details of the entire engine and considered it our responsibility to be so in order to create a world-class engine.

By April 1994 we could reveal more of the planned engine details, as the Lagonda Vignale and V12 show engine were garnering a lot of attention, whilst the V6 Mondeo was about to launch. I wrote much of the engine-related words for a more detailed press release that described the 60deg V12’s attributes and capacity — now officially a 6.0-liter — more in depth.

At the invitation of Jim Clarke, in mid 1994 John Oldfield (4) and Nick Fry (5) came to visit Advanced Powertrain and our new small team to review the progress on the rapidly progressing V12 being proposed for AML. There were no new engines installed and running, however, we arranged a host of high-performance vehicles (Ferrari, Viper, Mustang, Corvette and Porsche) to evaluate. We also had one of the earlier design, 90deg V12 Lincolns. There then followed detailed discussions on what we could really do to bring AML back in a big way. Publicly, the DB7 was having a strong positive response and deliveries were set for later that year. But the inline six was felt not to have the legs to sustain it in the long term. Ferrari was an obvious target, but fellow Ford family brand Jaguar had the new XK8 and a powerful supercharged XKR waiting in the wings. Both would be a problem for Aston Martin, so it was decided the first application for the new 60deg V12 would be in a DB7 Vantage.

The author with engine No. 1, for Indigo. No. 2 - for first DB7 - is visible in the rear.

It was an interesting time to be working on such an engine project. At Ford Motor Company our team had complete access to the data and designs for the Duratec family, which already had bespoke versions engineered by Porsche, Yamaha, Ford of North America, Ford of Europe and Jaguar. We endeavoured to make a unique V12 for AML, whilst leveraging many of Ford’s best resources.

Although not explicitly written out at the time, we developed guidelines for the new V12 that we stuck by:

1) Only use a component from another programme when it made sense and not compromise the design.

2) Version 1.0 (DB7 Vantage) would just be a starting point — the engine would be set up for lots of future power-growth potential, well beyond a ‘normal duty’ Ford engine. This would require significant design features.

3) Industry-leading in under-hood (bonnet) design. We would not cover the engine with ‘junk’ but make sure every part was functional and looked great for the long-term.

4) Redefining what a V12 could be: very high torque from low rpm, as well as high-revving power.

5) Making sure this unit was well designed to not only perform in the car, but be really well-thought-out for high quality and great value. If we could help AML be independently profitable, there would be funds available for a solid future.

6) Designing the engine to deal well with long-term storage and future rebuilds. After all, this was planned as a collector’s car.

There was one other closely held secret design condition. It was secret because management would not want us to ‘overdesign’ the V12. The truth is, with clever engineering, planning for significant power increases adds very little weight and cost if you know what you are doing and if it is done up front.

7) From the start, the V12 would be designed to compete at the Le Mans 24 Hours. Of course, the rules could change from when we started the design, but in principle the engine was designed from day one to be ready for racing. We knew if we did a good job the desire to take it racing would come. We also knew that Ford had a little bit of a tradition challenging Ferrari on the street and on the track!

The team was growing, and we added Scott Deronne to handle material (parts) control and tracking. One thing we still were not was ‘officially sanctioned’. We were going to have to run things differently because of that, for example the costs to tool the new unit came out of Jim Clarke’s Advanced Powertrain Engineering research budget, not as a sanctioned programme.

We realised one very important thing had changed that just might make this all possible. In the early 1990s technologies such as CAD (Computer Aided Design), CAM (Computer Aided Manufacturing), CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machine tools, computer simulation, rapid prototyping, etc. had come of age. This part of the AML V12’s history is a story all on its own. We were able to use these tools to design an all-new engine for a fraction of what was thought possible and that allowed us to proceed with Jim’s blessing to do this programme ‘under the radar’.

We soon needed to involve third parties for the sourcing of parts, offsite development and small-run manufacturing — tricky, as we had no official programme and suppliers were unsure they were going to see their participation rewarded by business in the future. But we convinced a dedicated group to give us a shot, starting with finding an assembly site suitable for a low-volume engine, something not possible in-house at the time, though we did try. Two candidates were in the frame: Cosworth, the leading contender, and long-shot outsider Uni Boring Inc. of Howell, Michigan. We invited both companies in for a detailed discussion for bidding on being the low-volume assembly site of a Ford-designed new AML V12.

Uni Boring was first up, and although a relative unknown we found their team really convincing; we liked the ‘can do’ approach backed up by a thorough in-person review of their team and facilities. Cosworth was the logical choice, especially given their deep relationship with Ford over many years. Our discussions with Cosworth merit a separate article but, in short — leaving out individual names — their representative’s attitude was: “Look boys, this is how it is going to work: Ford is too stupid to be able to design a good V12 for AML. Instead, you will give me a big bag of money and go away for about two years. At the end of that time Cosworth will come back with a shiny new V12 for you. We will design it, we will make it, and Ford will pay for it all. It is that simple…”

We made it quite clear that Ford was strictly looking for an assembly partner and that was it. When Cosworth’s proposal came in it purposely intertwined the design and manufacturing proposals so tightly as a single proposal that you could not get a number out of it that included only the manufacturing. What the Cosworth representative did not understand (or seemingly want to) was that even if we wanted to give them a ‘big bag of money’ it just was not there. We were ‘overhead’ in Jim’s organisation; part of his research budget. All he had to do — and even that part was a stretch — was start funding the V12 part by part. We threw out the Cosworth proposal and started working with Uni Boring.

Engine No. 1 nearly complete at Uni Boring.

Cosworth was stunned and protested loudly. It took them well over a year, but they finally got the decision overturned at the highest levels of Ford (to simply be the assembly site). By that time the engine design was completed and had passed durability testing.

Once this decision was made we needed to transition the assembly from Uni Boring to Cosworth. The on-site liaison from Cosworth assigned to help bring the completed design into Cosworth was Paul Ward. Although he didn’t know the details of exactly what had happened, Paul sensed the tension and did an exemplary job in a difficult situation. I count him and a number of the Cosworth personnel as friends today.

The rumour that Cosworth ‘designed the AML V12’ is simply untrue and really sells short the many dedicated people both within Ford Motor Company and throughout the industry that worked really, really hard to make this programme the success it turned out to be. I would, though, be remiss if I did not mention Cosworth’s participation in the engine’s calibration, not its design. Ford personnel were responsible for the new V12 strategy (software control algorithm) and Cosworth’s personnel, led by Graham West, jointly developed the engine calibration (software/engine tuning) with Ford personnel.

Although we used many of the best parts available within Ford, the V12 really is a unique engine designed for AML. I often ask people who state that it is simply two Duratec V6 glued, welded or taped together, “Have you driven a Duratec V6? And an AML V12? Do they sound the same? Does the V12 pull like two Duratecs?” I am certainly a fan of the Duratec V6s, but we knew we needed to do something more — a lot more, in fact — to truly make the AML V12 stand out. I did not know it at the time, but designing the magnesium Duratec V6 could not have prepared me better for designing the V12.

Cylinder block No. 1. Due to time, this was done on an open setup. CNC-machined parts had to wait until later.

Take the cylinder block for example. I struggled to make the magnesium 2.0-liter block work and now suddenly I had a material (aluminium) that was a third stronger and stiffer — no problem! The Duratec V6 is A319 cast aluminium with cast-in iron liners and a bed-plate bottom end. The V12 is A365-T6 aluminium, features a deep-skirt six-bolt main block, thin-wall press-in liners and directly mounts nearly all of its driven accessories. It features 3.0mm-larger (significant) main bearings, a bank-to-bank offset approximately 15mm less than the V6 and has a completely different casting design including a precision water jacket.

It’s a similar story for the cylinder heads. The Duratec V6s are from A319 cast aluminium, the V12s are A365-T6 cast aluminium with unique combustion chambers, a higher compression ratio, a precision water jacket and unique intake ports (one of the design features that significantly improved low-end torque whilst maintaining high-end power).

For the 1995 motor show circuit Ford showed the GT90 concept with the earlier 90deg, 6.0-liter Lincoln V12 by Jim Clarke and Bob Natkin, this time with (non-functioning) quad turbos. Claimed power was 720bhp at 6,600rpm.

This was the first ‘running’ Ford V12, but it remains a one-off and was never seriously considered for production.

The 60deg AML V12 continued to progress quite well and by September 1995 we were ready to fire it up. Unfortunately, Bob Natkin was at Le Mans with the GT90 doing a press drive and he was going to miss its first firing. We were working many long hours and Bob kept checking in via landline from France; email, cell phones and texts were not what they are today. By chance, Bob called right before we were about to attempt the first successful firing, and once we had the computer sorted it roared to life! We were very tired and only realised the next day that when the AML V12 ran for the first time it was heard not only at our test facilities in Michigan, but also at Le Mans. It was an excellent portent of its racing future.

Earlier that summer another ‘Ford supercar’ was hatched in parallel. Given the internal name ‘TSC’ (Technology Sports Car), this car was to be an extremely lightweight and technology-driven ‘showcase’. Subsequently titled Indigo, much of the venture was outsourced to RSVP (Reynard Special Vehicle Projects), and it was allocated the very first running AML V12, which was dry-sumped (with the oil pump now running on the defunct A/C position) and installed as the main structural member aft of the bulkhead. The DB7 Vantage was already an ongoing programme and engine number two went in the first car.

Indigo engine… almost. Actually, the display engine was a DB7 unit with Indigo exhaust and Ford nameplate.

Debuting at the North American International Auto Show (NAIAS) in Detroit in January 1996, the Indigo was shown at events throughout that year, though the accompanying display engines were straight production DB7 Vantage units except for the exhaust manifolds and the Ford V12 nameplate. We had no desire to reveal too much detail of the dry sump etc installation. As a nod to the forthcoming DB7 Vantage, we used the European spelling ‘litre’ on the nameplate after the Ford emblem instead of the traditional American spelling ‘liter’. The Indigo was a runner out of the box and had phenomenal press reviews with around 500bhp as installed.

We had Al English (the same gentleman who did the magnesium engine cutaway earlier for me) convert the intake and cam covers from raw castings to motor show-quality pieces. We worked closely with Al choosing the colour scheme for the show engines and liked it so much that the later powder-coated AML production parts used this original colour scheme as a basis.

Tom Walkinshaw Racing (TWR) had experimented with a 475bhp 6.4-liter Jaguar V12 in a DB7 around this time, but I was not aware of this car until I read about it in the press and I am not really sure how much TWR knew about the ongoing Ford V12 effort that was planned for the DB7 Vantage. When we read about it in the press there was no official reaction one way or the other.

The new Aston Martin V12 made its debut, presented as an AML engine for the first time, in Project Vantage — complete with motor show-quality Indigo intake manifolds by Al English — at the NAIAS in January 1998, one year ahead of the March 1999 Geneva Show reveal of the production DB7 Vantage.

I can easily see with all these V12s floating around that there were ample opportunities for confusion as to the origin of the AML V12 engine. I hope I’ve set the record straight.

The author next to an I6 DB7 at Bloxham - his first time in an Aston Martin.

Editor’s note:

The Trust and DesignJudges.com wish to thank Anthony Musci for this piece. Words and photos strictly copyright and with the kind permission of the author. Reproduction without permission forbidden.

In addition to his early start at Ford Motor Company’s Advanced Powertrain Engineering, Anthony has had a wide and varied career and has worked all over the world including Europe, Asia and the Americas. His vehicle development experience spans everything from high-volume production cars, to low-volume specialty vehicles to high-performance racecars. He has also worked across industries, including software and electronics in Silicon Valley, jet engine development, alternative energy, consumer products, and electronic control systems.

In addition to leading the design engineering on complex projects and vehicle development programs, Anthony is an experienced professional behind the wheel and has driven all kinds of vehicles as a test driver on open roads and test tracks all over the world. His experience is not restricted to the ground — Anthony has flown a wide variety of aircraft and holds pilot licenses for both rotary-wing (helicopter) and fixed-wing (conventional) aircraft.

Anthony has a Bachelor of Science in Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering from Rutgers University and a Master of Business Administration (MBA) from The University of Michigan — Ross School of Business.

Today, Anthony is VP Product Development and Technical Services at Cahill Services, LLC, a Private Equity funded start-up.

Footnotes:

(1) Ford owned the original Sorrento Blue show car until June 2002 when it was disposed of at a Christie's auction for $403,500. The second car was never fully engineered, used by Ford at various PR events, then scrapped.

(2) Code-named XM02 and subsequently numbered DP2138, it was built in 1995 and featured a V12 (Anthony Musci remembers it as a Jaguar unit). Intended to sound out the market for a production version and differing in many ways from the other two cars, DP2138 was later sold by Kingsley Riding-Felce to a collector in the Far East for $1.3m.

(3) Family owned since 1948, Eck Industries is based in Manitowoc, Wisconsin. Walter and Robert (Harley) Davidson were early investors.

(4) Who had, in February 1994, become executive chairman of Aston Martin.

(5) Managing Director at AML who had overseen the DB7 project.